Robert Gallagher, Wake

Remembrance as a Teacher - Inside the USSR

My father spoke Russian. That's why he was able to teach it. However, holding actual conversations with Russian speakers of various ethnicities and accents gave him different results than in class.

"Was she even Russian?" he wondered aloud when someone gave him directions in Moscow. He had said the same thing in Leningrad about the street directions he'd received there. "That sounded like a different slavic language."

At one point, he had a brief conversation with a Polish man who spoke Russian. That man had been lost and asked my father for directions. Naturally, my father couldn't help. They lingered to talk for a moment and shared common exasperations about the language they were using.

"He had a terrible accent. I guess I do, too," my father said as we got on our tour bus. He repeated the phrase again years later. "I think we understood each other better than anyone else we talked to."

Despite the relative innocence of our tour with high school teachers and their students, the Soviets restricted our itinerary sharply. They made only two cities available to visit, Leningrad and Moscow, with parts of them off limits. They assigned handlers to travel with the groups of students. They brought in KGB agents to trail after us and make sure we didn't engage in spycraft. My father once or twice suspected that the agents might be casually helping the tour. Certainly, there seemed to be plenty of kind Soviet citizens who helped students who got lost or who berated Russians when they were were rude to the students. There were helpful strangers to make sure everyone got on the bus or to stop the tourists from trying to buy snacks in the subway station and prompt them to run, quick, and get on the train with everyone else.

When we had breaks between tours of statues and basilicas, my father struggled with the Soviet transportation systems like everyone else. He had always loved the trolley cars in Baltimore, so at one point he decided we should take the trolley in Moscow as sort of a comparison. He lined us up at the stop after taking us on a walking trip for ice cream. It was going to be a straight ride back to the hotel.

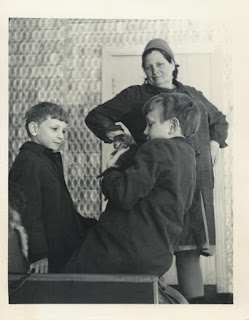

The trolley arrived. I leapt aboard and pulled my brother with me, his hand in mine. Behind, I heard a shout. To my father's surprise, the crowd would not let him follow. They pushed him out of the way and boarded the trolley until men were hanging off the outside. There truly was no room. Finally, one Russian man saw what had happened and that my father was struggling to get on the already full car. He grabbed my father by the arm and pulled him in. A wrestling match ensued between the man and the other passengers. The fellow barked something at the others. Although some of them barked back, they allowed him to pull my father inside the trolley car. He gave my father a push into the aisle in the general direction where I'd been carried by the crowd.

"Sometimes I do wonder about that guy," my father said later. "Was he an agent we hadn't noticed or was just a helpful person? Well, anyway, I'm glad he was there."