My father was born in 1934. His father died in 1936. For a while, he had a stepfather but that man and his mother said that they didn't like him. Before he finished first grade, he was homeless. Before he finished elementary school, his stepfather was dead. His uncle came to take him to Baltimore.

Since my father didn't have his mother's affection and mostly raised without his father, where did he get his ideas on parenting? In my twenties, I started to learn his family history, and I asked him about it.

"Mostly from psychology courses," was his answer.

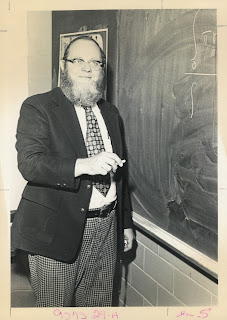

I looked through his library for major influences, probably Skinner and Maslow with a lot of Jung and Freud as well. In the psychological literature of his age, I noticed there was an overabundance of diagnoses of hysteria. Doctors thought that many people had psycho-somatic illnesses. In such circumstances, it was natural for my father to believe the same thing. Psycho-somatic illnesses appeared to be a proven cause. He was convinced that, when I was four, my mind caused allergies. My bouts of congestive failure were the result of the power of suggestion.

There is a certain amount of truth to this. Attitude makes a surprising difference to recovery. Over the years, though, my father observed that my attitude couldn't solve my physical problems entirely. In fact, ignoring my asthma sent me to the hospital more than once. So he let the doctors and scientists convince him that differences in immune responses are physical conditions, not simply products of the mind, and are are dictated in some part by genetics.

He learned as he went. That was his secret in teaching and that was how he did it with parenting. It wasn't simply a matter of translating theory into practice. He had to notice when the books were wrong. What's more, I think he passed over important elements of parenting in his own self-assessment. When I became a parent myself, I could see where some of his ideas had to originate. In reverse order of priority, I would say that his influences were:

3. His philosophy classes, psychology classes, and other reading (what he felt was most important)

2. My mother (although he didn't explicitly admit her influence until later in life)

1. His uncle, Jack Light

My great-uncle Jack spent a career in the merchant marines before settling down in Baltimore. When I was five or six or seven, I didn't know much about him except that I loved and admired him. In my childish view of the world, he was the most wholesome person in it. At the age of six, I came to understand that Jack was the only one who could stop my grandmother and my father from fighting. No one else had that power.

I have vague memories of my father once or twice saying that he couldn't be like Uncle Jack or that he didn't know how Uncle Jack did it. Jack had been so calm and so sure of himself, strong but gentle. He had the implacable force of patience that comes with self-assurance.

Jack died when I was seven. I begged to go to his funeral. Maybe I cried my way into attendance. I'm not sure. If so, I expect that my father regretted taking me because I cried at the funeral, too. Then I cried after the funeral and on and off through the evening.