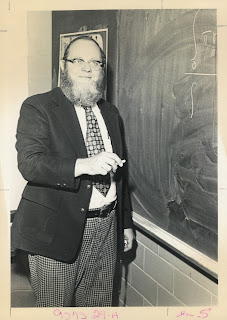

Robert Gallagher, Wake

When we got back to Maryland, my father settled into his teaching career with a grace that surprised even him, I think. In his personal life, he could be awkward. He could be too skinny. Or too fat. Maybe sometimes he dressed like a professor. As a teacher, he transcended all that. Students returned to tell him so. Some of them came with their revelations in psychology or philosophy. Those are personal subjects, of course, so maybe no surprise. Former students returned to tell him how his math teaching had improved their lives, though, and that seemed more remarkable.

Some of that may have come from how his teaching burbled with philosophy. Math and philosophy relate closely, particularly in boolean math, analytics, and other types of formal logic. So my father could, and did, use math to promote critical thinking. Additionally, he was a fan of Polya's "How to Solve It." He could switch from the county-promoted method to, for instance, solving a problem backwards. He tried to help students ease up from their frustrations by adopting a carefree oh-well-let's-try-this attitude.

One student I dimly remember returned to say how my father had transformed his life through math. This was a young man who had dark hair, stood maybe five foot eleven, and who as a student had caused trouble all through calculus class. Almost every day, he would say "This is useless" or "I'll never use it," and every time, my father had to come up with a reply like, "Maybe," "Maybe not," "The smart students will probably use it," or "Humor me. Maybe you'll need to fill a half-cylinder tub with jello."

This student was bright but he was politically-minded and stubborn. At the University of Maryland, he changed majors from journalism to engineering. Somehow he had been inspired by the practicality of making tangible changes in the world. But then his engineering friends, some of the same friends who had changed majors with him, started failing calculus. He didn't. He realized that he was going to use the math he'd railed against for so long, that he was using it right then. What's more, he understood it. He could even help other students. After he passed his required calculus, he came back and told my father.

There are only a few students who return to see their former teachers. Throughout the 1970s, my father seemed to hear from some every year. Even in the early 1980s, the trend continued. Northwood High school closed in 1985, unfortunately. My father transferred to Poolesville. The school was close to home. They needed precisely his position. The student body was different, though.

Although Poolesville students did return, at times, to tell him how good a teacher he had been, the numbers never quite matched Northwood. It was a smaller school and more rural. Fewer students went off to college and of those who did, many never came back.

No comments:

Post a Comment