Bryce Canyon

Star Talk

In the morning, I opened my suitcase to rifle through my stacks of t-shirts. The clothes we had brought for summer vacation didn't include winter sweaters or wool socks. We hadn't prepared for low temperatures at night in the mountains. In fact, we had only brought our jackets because we don't trust restaurants and their air conditioning settings. This proved to be correct thinking, as usual. But it also proved to be insufficient for desert stargazing.

I grabbed a fresh shirt. I didn't bother with the jacket because I knew it would be useless in an hour. I stepped into the same shorts I'd been wearing for a couple days.

"We have to get there early," I said with my hand on the doorknob of our bedroom.

"I know!" Diane grabbed her shoes. "I'm the one who set the alarm."

We arrived at the Bryce Canyon vistor center later than I'd hoped. When I counted the people in line for the Star Talk tour, I could see we wouldn't make it into the first group of tourists. We might not qualify for the second group, either. The visitor center had scheduled three tours. I thought we'd make it into the final one.

While we waited, we talked with our neighbors in line. We met a university professor from Colorado. She had three kids she'd persuaded to come along. We met a woman from Utah, who was on a camping trip with a friend. We met a man from New Jersey who seem sternly worried about his place in line, which was immediately behind us.

The New Jersey fellow counted up the invisible registrants - the missing children who were getting signed up, the friends still asleep at campsites - which I had done, too, and came to the same conclusion. We were probably not even in the second group. This was a popular tour.

"It's just four telescopes, fifteen people per group."

The name, Star Talk, made me hope we'd get lessons on cosmology. As we discussed the tour with our linemates, though, it sounded as if the Bryce Canyon staff would take us from telescope to telescope with no time for anything more than cursory questions. The park astronomers would aim the telescopes and pre-focus them. We would get a nice view but not much more.

"Have you gone hiking around the canyon?" the woman from Utah asked us.

"A little," I replied. "Today, we've got more planned."

"I'm looking for trails with some trees and shade," said Diane. "This trip has had too many hikes with no protection from the sun."

“Oh you can’t hike in the woods around here." The woman leaned back to laugh. "Everything is rocks!”

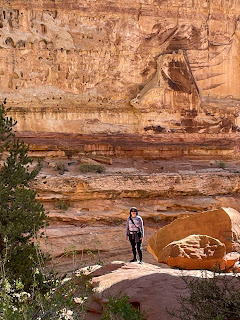

Diane and I knew that wasn't quite true, though. We had hiked the Yovimpe and its bristlecone pines. We knew half of the park is the Dixie National Forest. After we completed our Star Talk sign-up, which put us in the third group, as expected, we drove to a trail head. In less than twenty minutes, Diane found a path that lead down from the rocks into the forest.

We found pronghorn deer tracks, predator scat from a bobcat or some larger cat, a handful of the tiny squirrels I’d been mistaking for chipmunks, patches of flowers, goose poop, and a tiny stream where the pronghorn apparently came to drink. Probably all the animals did.

In the evening, we drove to the parking lot where the staff held Star Talk. Unfortunately, the tour really was just looking through telescopes. The staff had chosen Venus, which looked dull and blurry because it was low on the horizon and we had to peer through atmospheric interference. The next telescope pointed at the Hercules Cluster. The sight made me smile. The formation seemed utterly fantastic. I've had the opportunity to look into good telescopes several times but this cluster of T2 stars, more than 22,000 light years away, looked as beautiful as anything.

The next view was a computer-assisted take on the same Hercules Cluster. Horrible and disappointing, like an accurate but uninspired drawing. Finally, we strode to the last telescope, a view of the moon I've seen too many times before.

I was glad I'd lingered over the Hercules Cluster.

|

| Hercules Cluster via Wikimedia Commons |