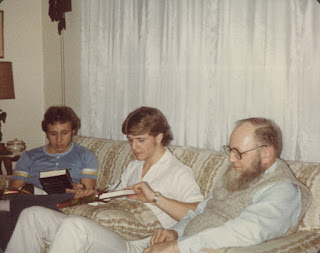

Robert Gallagher, Wake

Retirement

In a way, diabetes forced my father to retire. He had not planned on leaving his job. Even after fifteen years of sugar highs and lows, he persisted. He worked five years past retirement age. He ignored his treatment options and worked another year. That meant he had passed the mandatory retirement limit. Still, the county school system didn't force him to retire.

Since no one was stopping him, he worked another year. Then another. The county was supposed to push him out of his job but they didn’t have enough math teachers. He kept going. One day, after he ignored his medicine for a couple weeks and ate midnight snacks, he discovered that he had woken up at ten-thirty in the morning.

It was a Monday.

"That was the first day I've overslept for a teaching job, ever," he told me in shock. "The alarm must have have gone off. It wasn't broken. I tested it. But I slept right through the noise."

He'd heard strangers in the house when he woke. His co-workers had been keenly aware that he had never missed a day, had in fact never been late before. If you had given a Happy 68th Birthday party to someone a few months earlier and, one day, he didn't show up after a record like that, you might have had thoughts similar to theirs.

None of them wanted to check on him. Some of them, though, felt it was a duty that couldn't be avoided.

"It's better than having his family find him," was the prevailing opinion. So an assistant principal accepted the duty.

When he arrived at the house, the assistant principal knocked and got no answer. To his surprise, he turned the knob on the front door and found it open. But when he stepped inside for a moment, it didn't feel right. He backed out and closed the door. Instead of intruding, he ambled around the house and the deck. He tapped on windows. He peered inside whenever he could. From a window off the deck, he spied my father lying still and pale in bed.

"Bob." He tapped the window harder. "Bob."

He thought that he saw my father breathe. It was hard to tell. The vice principal stewed over it and made a decision.

He left. He drove to a payphone and returned after he'd gotten a police officer to agree to meet him at the home. He felt keenly in need of backup. He wanted help if my father was dying and he knew he had to be careful about appearances. That is how the vice principal and the police officer came to be in the house when my father awoke.

The officer, apparently, left after making sure my father was breathing normally. He checked for symptoms of a stroke, too, but otherwise departed without a word.

"I felt so groggy," my father told me later. "I don't remember the policeman, really. I only know that my principal told me that one of them had been there."

The assistant principal sat next to my father and talked to him for a while. My father must not have made a good impression. The fellow remained grim. He told my father to take the day off.

"Take more than a day," he said. "Go to a doctor about whatever this is, whether it’s diabetes or something else. When you've done that and feel recovered, come and see me."

It took my father a day to get an appointment and three days to return to school. When he went to visit the front office, the principal kept my father waiting while he called in his assistants. After twenty minutes, the last one arrived. They took seats around the big table.

The principal said, "Bob, we need to talk with you about retirement."

Although they allowed my father to return to Poolesville, he agreed to retire at the end of the year. However, that arrangement only lasted a couple of weeks. After the human resources personnel counted up his sick leave and personal leave, they realized that he hadn’t touched any of it for thirty years. His principal and vice-principals asked to meet him again.

"How's the new guy coming along?" the principal asked.

"He's all right."

"Good. Bob, I've heard from the county. They want you to use some of the leave you've built up."

"When?"

"Soon." He leaned closer. "Really, really soon."

My father returned to his classroom. He watched someone else do the teaching. He thought about the demand for him to retire.

He was already guiding his long-term replacement. The replacement was young but not a novice, not a first-time teacher. The students liked him but he wasn't a pushover for them, either. No one had any serious complaints about his work. After another week of observing, my father started taking days off. Soon, he took off for weeks at a time.

"I think I'm going to take off until the end of school," he said to me one time as we rested side by side in his easy-chairs. "I've got plenty to do around the house. Your mother is still teaching so I thought the days would be boring. But I’ve been doing a lot. The doctor says I should exercise more. I asked him if I could just do chores instead and he said, 'Sure.'"

"You saw the doctor?"

"He gave me some different medicine. I don't like it. It lets me get around the house a little better, though, and I know I need to take care of my eyes.”

“Did your eyes get worse again?” I knew that blood vessels had been bursting at irregular intervals in his corneas. When they did, the clots blocked his field of view. Sometimes, they rendered him blind for a few days.

“No. Better. My vision partly returned." He relaxed into a self-satisfied smile. "That’s why I could put shingles up on the roof yesterday.”

That made me sit up. He and my mother had been arguing about that job. I could hear her bumping around in the kitchen.

“I thought mom didn’t want you up there," I said. "She told me she was going to pay somebody.”

“Do you know how much they charge?" He snorted. "What a waste of money."

“Did she say anything about you climbing up?” Weeks ago, she had called to see if I could do it. With graduate school, a full-time job, and a kid, I wasn't up for it even on the weekends.

“She’s fine with it.”

“What I said, Bob,” my mother called from the kitchen, “was that I couldn’t stop you.”

“Well, it's the same thing, Ann.” He dropped his voice to a whisper. "She held the ladder."