Robert Gallagher, Wake

Remembrance as a Teacher - Overseas

When we were growing up, my father built a photo collage about six feet tall, three feet wide. I helped him put together the frame, the cardboard backing, and the photo pasting. That is, I was often in the same room. Since I was five years old, my help amounted to staying within sight and not stepping on the photographs as he pasted them. I'm not sure I succeeded entirely.

For years, I felt in awe of the collage. It was twice my height and wider than I could stretch my arms. My father hung it on the wall next to the stairwell.

On most days as I galumphed up and down the stairs beside it, I saw pictures of myself in Germany or of my parents on bicycles in Europe. There were pictures with relatives and others with friends. Oddly, there were also photographs without any of my family or relatives. They were small, square shots with rows of colored people in them, often colored and white people walking arm in arm together. Even when I was eight and had acquired a bit of context, I didn't understand those pictures of civil rights marches. My parents had gone to be in them. My father, as always, tried to document what was happening.

Even now, those poorly-exposed photos, fond memories for my parents, are blurry partial-recollections for me. Young black women in white dresses; four or five men seen from behind, one taller than others, his hair cut short to the shape of his head; a man in a suit raising his left arm with a small crowd in front of him.

The collage didn't survive moving between houses. My parents sorted the prints into cardboard boxes. They misplaced the boxes, or threw them out, or left them in forgotten corners of our basement where rescue cats peed on them. For my part, I didn't understand how the photos marked the end of an era for our family. After I was born, the civil rights marches continued, of course, but they went on without my parents.

Sometimes that's the reality of having children. I can understand that my mother may not have wanted to risk getting hit or hosed down by police while she had an infant in her care. In any case, my parents had started spending time overseas with their teaching jobs. The presence of children put an end to that too, in time.

When we were growing up, my father built a photo collage about six feet tall, three feet wide. I helped him put together the frame, the cardboard backing, and the photo pasting. That is, I was often in the same room. Since I was five years old, my help amounted to staying within sight and not stepping on the photographs as he pasted them. I'm not sure I succeeded entirely.

For years, I felt in awe of the collage. It was twice my height and wider than I could stretch my arms. My father hung it on the wall next to the stairwell.

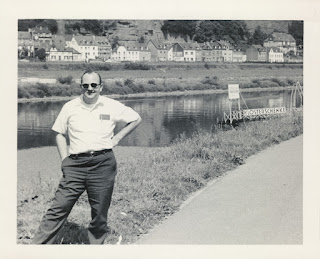

On most days as I galumphed up and down the stairs beside it, I saw pictures of myself in Germany or of my parents on bicycles in Europe. There were pictures with relatives and others with friends. Oddly, there were also photographs without any of my family or relatives. They were small, square shots with rows of colored people in them, often colored and white people walking arm in arm together. Even when I was eight and had acquired a bit of context, I didn't understand those pictures of civil rights marches. My parents had gone to be in them. My father, as always, tried to document what was happening.

Even now, those poorly-exposed photos, fond memories for my parents, are blurry partial-recollections for me. Young black women in white dresses; four or five men seen from behind, one taller than others, his hair cut short to the shape of his head; a man in a suit raising his left arm with a small crowd in front of him.

The collage didn't survive moving between houses. My parents sorted the prints into cardboard boxes. They misplaced the boxes, or threw them out, or left them in forgotten corners of our basement where rescue cats peed on them. For my part, I didn't understand how the photos marked the end of an era for our family. After I was born, the civil rights marches continued, of course, but they went on without my parents.

Sometimes that's the reality of having children. I can understand that my mother may not have wanted to risk getting hit or hosed down by police while she had an infant in her care. In any case, my parents had started spending time overseas with their teaching jobs. The presence of children put an end to that too, in time.

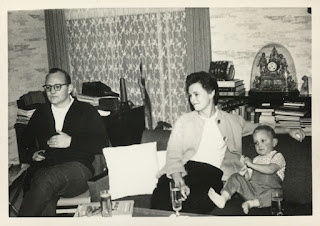

At first, my parents kept their careers as civilian, federal employees of the US Army. Only my mother flew to Maryland for my birth. A few months later, she returned to my father in Germany, this time to his posting in Hamburg.

At first, my parents kept their careers as civilian, federal employees of the US Army. Only my mother flew to Maryland for my birth. A few months later, she returned to my father in Germany, this time to his posting in Hamburg."I did start to like teaching," my father said of his time at the army bases. "You could get up in front of a class and tell jokes and everyone felt compelled to laugh."

His students enjoyed his lectures. They talked to him at length after classes. He got to explore subjects he liked: philosophy, psychology, and the Russian language. The head of the faculty pressed him into teaching math as well. He hadn't paid much attention to the subject in college, only enough to get through calculus, but he found that he enjoyed talking about it. It felt to him like philosophy but more rigorous.

Meanwhile, my mother started pressing for a return to the United States. She was lining up better paying jobs in Maryland, ones with union benefits like parental leave. She was tired of moving from post to post. In Maryland, they had bought a home in 1961. But they barely lived in it before they accepted jobs in Europe. Their realtor had offered to rent it out for them, so the mortgage kept getting paid, and it was still theirs.

They returned to that house in College Park in the summer of 1966. That gave them a month to decide on their new teaching jobs.

No comments:

Post a Comment