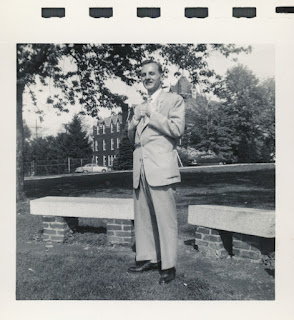

Robert Gallagher, Wake

When Robert Roberts walked down the stairs of the US Army discharge facility, he stepped onto the dirt of Monterey, California. He held a severance check in his hand. He didn't know where he could stay but he had a little time to find a room and a job.

Without any particular sense of direction, he worked as a floor referee in a roller rink where he learned to skate backwards and dance on skates, as a grocery clerk, as a blackjack dealer in Las Vegas, and in other occupations, each for a few weeks or a few months. He liked moving from place to place. He changed jobs and towns in quick succession until a high school friend got married. Doris asked him to be an usher in her wedding back in Baltimore, which is when he headed back east.

After her wedding, he tried being a real estate broker in a Baltimore bank, a clerk for a law firm, and a stockbroker for Baker and Watts. He hired on as a pressman for a printer, a day laborer for a construction company, and as a cement mixer for roads and buildings. (Once, as we drove out of the way on a camping trip, we passed over a bridge my father help build. He shrugged to my mom and admitted it was ugly but he was happy to see it in use.)

One of his friends told him that a college might accept him as a veteran even though he hadn't finished high school. He was eligible for the GI Bill. So he put in applications at Georgetown University and Maryland University. Georgetown asked for more paperwork. He sent it to them but he didn't hear back. In contrast, he skipped his orientation meeting for Maryland but they sent him an acceptance package. He figured, "Well, this is where I'm going."

Two weeks into the fall semester, he got a letter from Georgetown saying, "Why didn't you show for your orientation?" It turned out they had admitted him, too, but they hadn't sent a notice.

Undergraduate Remembrance

Unlike the younger students, my father had never graduated from high school. He felt underqualified and self-conscious about it. He stood out in other ways, too. As a freshman, he was older than the college seniors. In his class picture of nine hundred, there were two men with beards. One of them was my father. The other was a professor. Those were reasons he knew he had to work harder. In fact, he took so many classes and did so well that he realized he could get his bachelor's degree in three years. That would leave him room on his GI Bill eligibility to get a master's degree.

Unbeknownst to my father, a young woman from Annapolis had won a double-handful of academic scholarships to University of Maryland - my mother, Elizabeth Ann Stockett.

Ann had gotten straight As in her high school. Her level of achievement plus an essay and an interview won her a Senatorial Scholarship, one of two given each year. She won other scholarships to cover her books and living expenses. In fact, she qualified for so many financial awards that she had to give some of them away.

My parents were both interested in languages, psychology, and philosophy, so they ended up in the same social circles. Also, for the first time in his life besides the signal corps school, my father was studying hard. Or so he thought until he compared himself to Ann.

Ann had suitors and flatterers around her. Some drove from military bases to see her. Others bought her gifts. Some tried to get her drunk. One tried to climb into her dormitory room. My father watched from a distance for a few weeks and listened to her tell stories and laugh about them.

They hung out in their large, loosely-knit circle of friends with John Palmeroy, Betsy Friedman, Bob and Sybil Sampson, Dick Spotswood, and many others. Some of their friends gained local prominence, later. (Dick Spotswood hosted a radio show.) Two years ahead of them in the same disjointed crowd was "the puppet guy" who went on to create commercials, local television shows, and eventually The Muppets. His name was Jim Henson.

Note: my parents were sure that although Henson was nice enough, he was destined for obscurity. He was playing with puppets, after all. That's why, in 1962, they agreed on two possible names for me: Kermit and Eric. I'm grateful they chose Eric, since The Muppets ended up not being so obscure.

For a while, my parents merely hung out in each other's general vicinity. My father clued in, eventually, that "Ann didn't like any of her suitors." Somehow, with her help, he asked her out.

"We went on one group date and suddenly we were a couple," is how he put it later. "What I didn't know is that your mother had already made up her mind about me."

Pretty soon, they started plans to live together and marry. It didn't slow down their advancements through school. They shared a group house off campus. My father worked as a librarian for the university, then as a librarian and clerk for the American Philosophical Society. He took more philosophy and psychology courses, plenty of English and history, and learned from my mother's study habits that he had been taking it easier than he'd realized.

great read :-)

ReplyDelete